Mandrakes and Three More Children for Leah

The matriarchs hold a special place in the Hebrew canon and society. They are so much more than “Jacob’s wives” or “the mothers of the Children of Israel.” To this point, we have discussed when Rachel and Leah met Jacob, Leah’s loveless marriage and her first four children, and the enslaved matriarchs Zilpah and Bilhah. Now, we will discuss a bit about Rachel and Leah’s relationship and the birth of three more children for Leah, the result of the exchange of mandrakes for sex.

An Exchange of Mandrakes

Genesis 30:14-15 is the first to have a dialogue between Leah and Rachel.

“In the days of wheat harvest Reuben went and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them to his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, ‘Please give me some of your son’s mandrakes.’ But she said to her, ‘Is it a small matter that you have taken away my husband? Would you take away my son’s mandrakes also?’ Rachel said, ‘Then he may lie with you tonight for your son’s mandrakes.’”

In many ancient cultures, mandrakes were considered an aphrodisiac. This would explain Rachel’s desire for the “love-apples,” as they were sometimes called. After Reuben, Leah’s eldest, came in from the field with mandrakes, he delivered them to his mother. This brief scene sets the reader up for the first dialogue between Leah and Rachel, and the first time Leah even acknowledges Rachel in the text.

Rachel requested that Leah give her some of Reuben’s mandrakes. Rachel approached Leah in a polite fashion; she even said please. Leah, however, was not so pleasant. She sharply replied, “Is it a small matter for you to take my husband? And would you take my sons mandrakes also?” (30:15). Jeansonne notes, “This statement indicates that as the second but more beloved wife, Rachel has usurped Leah’s position of privilege as first wife and firstborn. It also indicates that at some point in the marriage Rachel has obtained sexual monopoly of Jacob.”1

Rachel responded by using Jacob as a bargaining tool. She offers to exchange one night with Jacob for Reuben’s mandrakes. And Leah agreed. Rachel’s response indicates three things.

1. Rachel had more control over Jacob’s sexual activity than Leah, and perhaps even Jacob.

2. Leah did not have the same type of access to her husband as Rachel.

3. Rachel is in control of the entire situation. She knew what to offer in order to get what she wanted.

Rachel wanted children, and the mandrakes could be a means to that end. Leah wanted Jacob, and the giving up of the mandrakes was the means to that end.

Leah’s Hired Husband

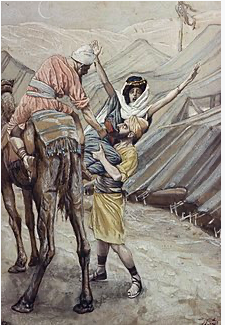

The interesting twist in the story comes in 30:16.

“When Jacob came in from the field in the evening, then Leah went out to meet him and said, ‘You must come in to me tonight, for I have surely hired you with my son’s mandrakes.’”

Jacob is passive and objectified. In the same way that the sisters were objectified by Laban in 29:21-25 on the wedding night, so Jacob is powerless. He is completely silent and simply does as he is told. The next verse explains just how productive that one night was: “…she conceived and bore Jacob a fifth son.”

Issachar

This fifth child, Issachar, is born. The speech, “God has given me my hire because I gave my maid to my husband” is a direct response to Leah’s the giving of Zilpah to Jacob, and the “hiring” of Jacob for the night.

Leah seems to be gloating. She acknowledges the favor of God in her pregnancy because she gave her maid to Jacob, but Rachel also gave her maid to Jacob and is yet without children.

Zebulun

Leah’s one night with Jacob clearly does not stop there. After the birth of Issachar, we are told that Leah conceived again. The text says she bears Jacob a sixth son: “God has endowed me with a good gift; now my husband will dwell with me, because I have borne him six sons.”

It is interesting that, after giving Zilpah to Jacob as a wife and naming her children for her in a way that suggests adoption, her naming speech mentions only her six sons.

The naming of Zebulun is also reminiscent of the namings of Reuben and Levi. In all three she hopes that the child will cause her husband to cling to her in a way that he hasn’t yet. After all three, the reader is left assuming that Jacob has not changed.

Dinah

As a sort of encore performance, Leah delivers a baby girl. Dinah has no naming speech. Her birth announcement is sort of an afterthought.

An Epitaph for Leah

From this point on in Genesis, Leah virtually disappears, with her death being reported at 49:31. She is absent from the narrative recounting the rape of her daughter Dinah and Rachel’s death scene, though Jacob requests to be buried with Leah, not Rachel, in 49:29-33. Gafney writes:

Leah the loveless matriarch is a heartbreaking character…There is no happy ending for Leah; she is not fulfilled as a person or as a woman in motherhood. She is not the last woman to go to her grave longing for the love of a man who does not love her but is willing to sleep with her. Pious women readers/hearers may not choose to be Leah, but I suspect Leah’s story canonized her lovelessness as well as her fruitfulness because it rang true to human experience. Leah offers a cautionary tale to women looking for fulfillment in someone else’s love: you cannot make someone love you.[2]

2. Wilda C. Gafney, Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne (Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, 2017), 66-67.

5 thoughts on “Mothers of the Children of Israel (5)”